I came home from work today and I cleaned up the kitchen. Why did I do it? I wanted to, the mess from my dinner party last night, still left in the washing-up basin, quite frankly, I found quite repulsive. I guess my housemate would have done it when he came home, but I did it of my own accord. What I just described was, according to Long (1985:), what is summerised as a task:

“a piece of work undertaken for oneself or for others, freely or for some reward. Thus examples of tasks include painting a fence, dressing a child, filling out a form, buying a pair of shoes… in other words, by ‘task’ is meant the hundred and one things people do in everyday life, at work, at play and in between”

However much one might like to dream, nobody gets their Intermediate evening class to do the washing up – I hope not anyway. Ellis (2003: 16) jumps in with a more specific definition of what a pedagogical task is:

“A task is a workplan that requires learners to process language pragmatically in order to achieve an outcome that cane be evaluated in terms of whether the correct of appropriate propositional content has been conveyed. To this end, it requires them to give primary attention to the meaing and to make use of their own linguistic resources, although the design of the task may predispose them to choose particular forms. A task is intended to result in language use that bears a resemblance direct or indirect, to the way language is used in the real world. Like other activities, a task can engage productive or receptive, and oral or written skills and also various cognitive processes.”

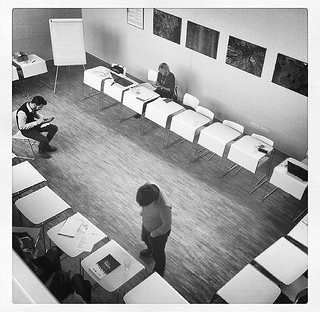

In a recent seminar on TBLT, I asked participants to make a top-five list of their favourite restaurants in Berlin. The next task I gave them was to make a call to another participant and invite him or her to one of those restaurants, give a summary of the menu, make arrangements and give directions.

Would they do that in real life?

Was there a goal or outcome of the task?

Was their primary outcome the language they wanted to use or the aim of the task?

What were the main forms used to complete the task?

Funnily enough, in the first task lots of language was thrown up in the discussion relevant to the next task: “it’s a bit pricey, anything up to €20 a head”, “It’s closed on Mondays but you can go any other day of the week”, “It’s a kind of Thai-Vietnamese fusion”, “kofte, kebab, that kind of thing”, “you know that bridge near Kottbusser Tor, it’s near there, just down the road and on the left, next to the supermarket”. In the second task, participants reused the same forms again, with the small addition that they had to negotiate when was a good time to go out to dinner.

They were, I have to admit, all native speakers – so let’s face it, choosing the right linguistic forms wasn’t much of a challenge. Had they been learners, the negotiation of meaning would have occurred in the during task phase, as Lightbown and Spada Lightbown & Spada (2006: 150) write:

“When learners are given the opportunity to engage in interaction, they are compelled to ‘negotiate for meaning’… the negotiation leads learners to acquire the language forms – the words and the grammatical structures – that carry the meaning they are attending to”

But – and this is a pretty big but – even if you think you’re running a really tight ship, leaks can still occur and it shouldn’t be taken for granted that a well-designed task alone will smooth over all gaps in meaning; while learner are attending to meaning, breakdowns in understanding can occur.

The tasks were appropriate according to their aim: the first was intended to prime participants for the language forms to come by performing a similar task with the aim of brainstorming places to go for dinner and the second provided the outcome of making arrangements for dinner. I picked two boxes from the task cycle I drew up below:

While reading around, I found that there were many different types of task cycle proposed by Nunan, Jane Willis and Ellis so I took elements of all of them and fused them together in attempt to try and make a more comprehensive map. I feel it’s important to note that TBLT works best when it exploits the right blend of component parts of the task cycle appropriate to the task, the level of the class, the materials (if) used external requirements on the course.

While reading around, I found that there were many different types of task cycle proposed by Nunan, Jane Willis and Ellis so I took elements of all of them and fused them together in attempt to try and make a more comprehensive map. I feel it’s important to note that TBLT works best when it exploits the right blend of component parts of the task cycle appropriate to the task, the level of the class, the materials (if) used external requirements on the course.

Of the parts in the task cycle, arguably the most important in terms of learners’ linguistic development is a Focus on Form. This idea differs from the Form-focused instruction found in PPP methodology in as much as it focuses on the salient forms that emerge from the task, i.e., those immediate to the learners’ communicative purpose. The advantage that this proposes is that by achieving a task that has a meaningful communicative purpose, while receiving (overt) support from their teacher in doing so, learners will retain language better.

It’s quite right to say on the hand that if not correctly implemented, TBLT will swerve away from the well-intentioned rationale stated and veer dangerously towards pedagogical nothingness – an important consideration to bear in mind when designing a lesson. What this means is a TBLT lesson requires a lot of thought about the right tasks tailored to the learners’ communicative needs and a teacher equipped with the right tools to second-guess relevant forms and be prepared to clarify emergent language.

Doughty, C., & Williams J., Focus on Form in Classroom Second Language Acquisition, Cambridge Applied linguistics, 1998

Ellis, R., (2003). Task-based Language Learning and Teaching. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N., How Languages are learned, Oxford University Press, 1996

How can I cite your Task cycle framework? I do like it and I’d like to use it in an easy on TBL.

Feel free to, yes.